Redmile to Woolsthorpe Wharf

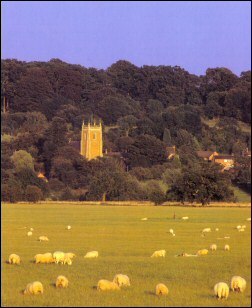

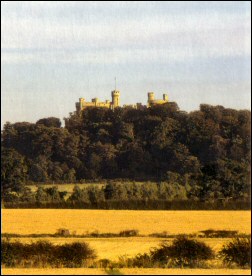

The whole of this section from Redmile to Woolsthorpe is a footpath and, as it crosses this last part of Leicestershire and enters Lincolnshire, the canal takes on what must be something like its original atmosphere. There are long open stretches of water with the appearance of being navigable and several high, arched bridges, with the towpath for the barge horses passing underneath. These have been restored with matching brick to reproduce those built originally in the 1790s. The views are dominated initially by Bottesford church to the north, but later and more dramatically Belvoir Castle appears to the south. This section too gives an excellent sense of the contouring route which the canal surveyors devised, with fields to the left sloping downhill and fields to the right sloping up.

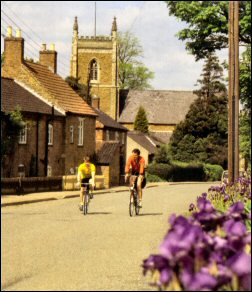

Redmile, entered in the Domesday Book as `Redmelde’, the `place of the red earth’, has an air of rural calm and antiquity. The early English stone church of St. Peter’s glows whenever the sun shines and, aided by the wide south aisle and sparse furnishings, it vividly retains the atmosphere of the 13th century when it was built, and a time when churches were used for far more activities than just worship. The lovely gilded clock was restored for Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee in 1977.

Redmile, entered in the Domesday Book as `Redmelde’, the `place of the red earth’, has an air of rural calm and antiquity. The early English stone church of St. Peter’s glows whenever the sun shines and, aided by the wide south aisle and sparse furnishings, it vividly retains the atmosphere of the 13th century when it was built, and a time when churches were used for far more activities than just worship. The lovely gilded clock was restored for Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee in 1977.

Like most villages, Redmile was self sufficient in crafts and services until the end of the last war. Now the shops have gone, their presence in the main street only betrayed by the extra large windows in some of the cottages. A curious bit of local history concerns the rector in the village around 1660, Thomas Daffye, who achieved notoriety as the inventor of Daffy’s Elixir. Advertisements claimed this to be “a certain cure, under God” for practically every medical condition known to man, but also to “being a noble cordial after hard drinking”.

On rejoining the towpath, Redmile’s church and picturesque pantiled roofs are soon left behind. Almost immediately a winding place is passed as, lined with iris and purple vetch, the towpath swings north, then northeast and north again beginning its long loop to negotiate Toston Hill. Bottesford church is glimpsed through gaps in trees – at one point directly ahead. At Bottesford Bridge [B55] an open area and access lane are the only remains of the Bottesford Wharf. Cross the lane close to the curiously named `Thisisit’ house and within a few yards the towpath has swung round to head southeast through a cutting which slices through the tip of Toston Hill. This avoided creating the obstacle of a sharp unnavigable bend had the true contours been followed.

On rejoining the towpath, Redmile’s church and picturesque pantiled roofs are soon left behind. Almost immediately a winding place is passed as, lined with iris and purple vetch, the towpath swings north, then northeast and north again beginning its long loop to negotiate Toston Hill. Bottesford church is glimpsed through gaps in trees – at one point directly ahead. At Bottesford Bridge [B55] an open area and access lane are the only remains of the Bottesford Wharf. Cross the lane close to the curiously named `Thisisit’ house and within a few yards the towpath has swung round to head southeast through a cutting which slices through the tip of Toston Hill. This avoided creating the obstacle of a sharp unnavigable bend had the true contours been followed.

There are the remains of a lengthman’s hut in the cutting. Continue to the next road at Easthorpe Bridge [B56], formerly known as Middlestile Bridge. You will have reached the three-quarter mark of the walk. A `short’ mile brings you next to [B57]. Note that there is yet another spot height of 44 metres here – the same as at Fosse Bridge. This is Muston Gorse Bridge and the canal noticeably widens here too.

Muston Gorse was the wharf for, and terminus of, the Belvoir Tramway. It was from here that the Duke of Rutland proposed to build a 1½ mile branch canal to terminate in Belvoir Castle grounds. Persuaded that the gradients were so severe and that the number of locks required, not to mention the question of a water supply to feed them, made the project unfeasible, he settled for a horsedrawn tramway instead. This was constructed to a 4 foot 4 inch gauge in 3 foot long ‘fish belly’ rail, so named because the central portion of each rail was thicker to give additional strength.

The tramway was a very `modern’ design for its time, in as much as the flanges were on the wagon wheels rather than the track as earlier wagonways had been. Also, the idea of laying metal rails, rather than wooden ones, was so alien to the first gang of workmen engaged that they refused to undertake the work. It was not completed until 1815, some 18 years after the canal opened, but had a useful life of 100 years, ceasing to operate around 1918.

Traffic was made up of coals and general supplies solely for the castle. Lengths of the track are preserved in the Science Museum in London and at York Railway Museum.

Traffic was made up of coals and general supplies solely for the castle. Lengths of the track are preserved in the Science Museum in London and at York Railway Museum.

Belvoir Castle itself is perched some 135 metres (400 feet) up on a spur of Blackberry Hill. The first castle was built by Robert de Todeni, standard bearer to William the Conqueror, and his descendants held the castle until 1247. It then became the property of the de Ros family, but after the Wars of the Roses, in which the Ros’s had supported the Lancastrians, they were out of favour with Edward IV and in 1464 Lord Ros was hanged. It became ruinous under its new owner Lord Hastings, who even had some of the stone carted away. Once the castle was inherited by the Manners family (and they are still the Dukes of Rutland), rebuilding began around 1523 and lasted for some 30 years

All this was undone yet again a century later for Belvoir was `slighted’ again in 1649 during the Civil War. Rebuilt once more between 1654 and 1668, it was remodelled after to give a more medieval appearance. A fire in 1816 badly damaged much of the northeast corner but that was soon rebuilt.

Over the centuries the castle has been the scene of hospitality to many members of the royal family and contains many fine rooms filled with family portraits and belongings, together with other artworks. The castle and gardens are open to the public between March and October.

Just beyond Muston Gorse Bridge, the Knipton Feeder enters the canal on the far bank. The Knipton Reservoir covers an area of 52 acres and was constructed as the primary supply to the 20-mile pound. It lies 2 miles south of Belvoir Castle behind Blackberry Hill and from it emerges a stream known as `The Carrier’. This tunnels under the hill for about a mile, resurfacing on the Leicestershire/ Lincolnshire border.

Continuing via Longore Bridge [B58] with its name painted underneath, we cross the Leicestershire/Lincolnshire county boundary, where there is another winding hole, to reach Muston Bridge [B59]. Canada geese are sometimes visitors to this part of the canal. The ironstone railway, built to exploit the iron deposits around Denton and Harlaxton, comes in on the left from its nearby junction with the main line. Its presence becomes more obvious as we proceed towards Woolsthorpe.

Very soon after Muston Bridge we come to the end of the 20-mile pound at [L12], the first in the sequence of seven locks known as the Woolsthorpe Flight. It is followed in quick succession by two more locks [L13] and [L14]. These begin the gradual rise of the canal which enables it to penetrate the gap in the hills ahead and reach Grantham; these lower locks are at present unrestored. A mile-long straight towards Woolsthorpe now opens up beyond Stenwith Bridge [B60], the arch of which encloses a striking view of Belvoir Castle.

Very soon after Muston Bridge we come to the end of the 20-mile pound at [L12], the first in the sequence of seven locks known as the Woolsthorpe Flight. It is followed in quick succession by two more locks [L13] and [L14]. These begin the gradual rise of the canal which enables it to penetrate the gap in the hills ahead and reach Grantham; these lower locks are at present unrestored. A mile-long straight towards Woolsthorpe now opens up beyond Stenwith Bridge [B60], the arch of which encloses a striking view of Belvoir Castle.

By the next lock [L15] the Viking Way has joined in from the left too, using the towpath as far as Longmoor Bridge beyond Woolsthorpe. The remainder of the Woolsthorpe Flight soon appears framed in an avenue of trees as Woolsthorpe Wharf and the Rutland Arms are approached. On the far bank just before the inn stands a range of buildings known as the Carpenter’s Shop G In fact they comprised a general workshop and stores complex for the maintenance of the canal, with an office, a sawpit and stables together with blacksmiths and carpenters facilities. They were restored in 1994.

An Anglo-Saxon settlement is known at Woolsthorpe from remains dug up in the 1880s when ironstone mining began just north of Brewers Grave. The village has since shifted down into the valley of the River Devon. Its church dates from 1791 (rebuilt 1854) as the earlier one was destroyed during the Civil War.

The Rutland Arms H was certainly here and patronised by the bargemen when the canal was operational, and takes its name from the Dukes of Rutland at Belvoir Castle. It has long had a second name, being known as the `Brown Duck’ until at least the 1930s. Nowadays its signs feature the more prosaic alternative name of the `Dirty Duck’.