History

Chronology

Before the Canal

In the 1760’s Lincolnshire coal was transported to Grantham via the Trent and then by road. The road haulage was relatively expensive and so coal in Grantham could be twice the price of that in Nottingham.

Canal Proposed

In 1792, pressure from the businessmen of Grantham resulted in a Bill to Parliament proposing a canal to transport coal from Nottingham to Grantham. This Bill was defeated by pressure from several sources. These included the Witham Navigation Commissioners, who feared it would deplete their water levels and the Lincolnshire coal merchants who feared a threat to their business. A revised Bill, which included measures to allay these various fears, was put before Parliament in 1793 and received Royal Assent in April having passed the whole gamut of legislative procedures in less than a month! The Act enabled the Proprietors of the Grantham Canal Navigation to raise working capital of £75k with a further £30k as a contingency. The money was raised rapidly and work started the same year.

1797 – Canal Opened

The work was completed in 1797. The canal started near Trent Bridge and was 33 miles long and rose 140 feet up to Grantham through 18 wide locks. In addition to coal, the canal carried various bulk materials such as stone and lime and, rather less obviously, ‘night soil’. The canal company rarely achieved its maximum allowed dividend of 8% but nevertheless, by 1806, was producing a small but steady return. The peak year was 1841 when receipts rose to £18,000.

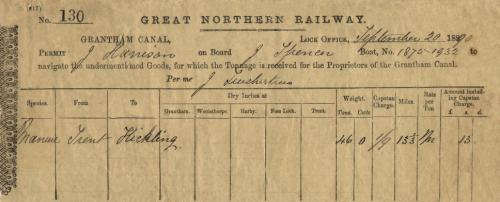

Above is a toll receipt of 1890. The cargo is ‘night soil’. Note the ‘capstan charge’ of 1/9d (8.75p) This was levied for hauling the boats from the fast moving waters of the River Trent into the Grantham Canal.

1830 – Competition from the Railways

From 1830 the railways began to make inroads into the profits. The opening of the Grantham to Nottingham railway in 1850 foreshadowed the eventual demise of the canal. In 1861 the railway company obtained control of the canal. By 1921, after a series of mergers and takeovers, control was vested in the London and North Eastern Railway Company. It is interesting to note, however, that while the two main railway bridges crossing the canal near Plungar are dismantled, the canal is still intact!

1936 – Closure Act

A Closure Act was passed in 1936 but with the proviso that a two foot level of water should be maintained to support agricultural needs.

1950s – Vandalism!

In the 1950’s all but 23 of the 69 bridges over the canal were flattened to make way for road improvements. Some saw this as exigent, others as nothing more than legalised vandalism.

Above is a typical example of a dropped bridge. The water flow is through two concrete pipes. These dropped bridges are one of the major challenges facing the canal restorers – the others being the link to the Trent and of course, the locks.

In 1947 the railways, and hence the canal, were nationalised.

In 1963 control of the canal passed to British Waterways

1968 – Canal ‘Remaindered’

In 1968 the canal was placed into a ‘remaindered’ state. This reduced the amount of maintenance the owners of the canal were obligated to do in law. It is perhaps interesting to note that the Grantham fared better than some canals where, in some cases, the line was totally obliterated.

The canal’s future looked bleak. The line of the canal was severed by a railway embankment at Woolsthorpe, locks fell derelict (with concrete weirs installed to control the water levels) and many hump-backed canal bridges were replaced by concrete pipe culverts with flattened decks.

The Grantham Canal Restoration Society was formed in 1969 and in collaboration with British Waterways, the Inland Waterways Association and the Waterway Recovery Group, began the long road to full restoration. Early successes were the award winning slipway at Denton, the removal of the railway embankment at Woolsthorpe and the restoration of the top three locks of the Woolsthorpe flight. The restoration section of this website has detailed accounts of these achievements.

With restoration gathering pace, it became clear that full restoration was going to involve many organisations – the GCRS, BW, the IWA, local authorities and the newly formed Grantham Navigation Association. Understandably, there were a few organisational problems. These groups were all brought together with the formation of the Grantham Canal Partnership, an umbrella organisation which everyone concerned with the canal reported to.